In honor of Black History Month, also known as African American History Month, we are celebrating the contributions of African Americans, not just to our country’s history and culture, but to the legal profession. These black lawyers changed the world by shaping the landscape of the law in the United States, and changing perspectives of racial equality everywhere. Don’t forget to watch the accompanying video at the end of this post.

Macon Bolling Allen: First African American Lawyer and Judge in the United States

In the 1840s, Allen, a schoolteacher from Indiana, began an apprenticeship to a prominent attorney and abolitionist in Maine. His boss encouraged him to take the Maine bar examination, and in 1844, Allen became the first African American man licensed to practice law in the country.

It was difficult for a black man to attract clients in mostly white Maine, so he moved to Boston, but continued to encounter racism there. Undeterred, he passed a rigorous examination to become a Massachusetts Justice of the Peace, or civil court judge.

The 1848 Dred Scott ruling meant Allen was not considered a U.S. citizen, but he still became the first black judge in the U.S.

After the Civil War, Allen moved to South Carolina and became a partner in the first U.S. law firm led by black individuals. In 1874, he was elected as a probate court judge in Charleston County, where he served until 1878. He later moved to Washington D.C. as an attorney for the Land and Improvement Association. Altogether, Allen worked in the legal profession for 50 years.

Charlotte E. Ray: First Female African American Lawyer in the U.S.

Raised in a progressive family, Ray attended one of the few schools in the country that allowed black women at the time. She went on to train as a teacher at Howard University, a historically black college in New York. But Ray wanted to practice law, so she began taking law classes there. It is said that she applied for the bar under the name “C.E. Ray” to disguise her gender; others dispute this, as the bar had recently begun admitting women. Either way, in 1872, she became the first black woman to earn a law degree and practice law in the U.S.

Ray began an independent commercial law practice and was known for her authoritative legal knowledge and eloquence when arguing cases. Although she was said to be “one of the best lawyers on corporations in the country,” due to racial prejudice and sexism, she couldn’t attract enough clients to support herself. She became a teacher and an activist for women’s suffrage and equality for black women.

Jane Bolin: First Black Woman to Graduate from Yale Law School and Become a U.S. Judge

When Jane Bolin was at Wellesley College, an advisor discouraged her from applying to Yale Law School, because of her race and gender. She applied anyway and was accepted.

When Jane Bolin was at Wellesley College, an advisor discouraged her from applying to Yale Law School, because of her race and gender. She applied anyway and was accepted.

At the time, she was the only black woman in her class. She graduated in 1931, and a year later, passed the New York City Bar examination and began practicing law. In 1939, when New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia appointed her to a judicial position in the Domestic Relations Court, Bolin became the first black woman to serve as a U.S. judge.

She served on the Family Court bench for four decades, advocating for racial justice and children’s rights.

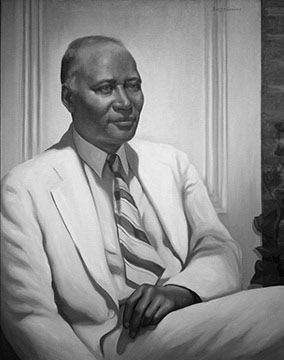

Charles Hamilton Houston: “The Man Who Killed Jim Crow“

When Houston, an English professor, was a First Lieutenant in the U.S. Infantry in World War I, he experienced such blatant bigotry that he vowed to “study law and use my time fighting for men who could not strike back.” He enrolled at Harvard Law School, and became the first African American to serve as editor of the Harvard Law Review. He earned a Juris Doctor degree in 1923 and joined the Washington, D.C. bar in 1924.

When Houston, an English professor, was a First Lieutenant in the U.S. Infantry in World War I, he experienced such blatant bigotry that he vowed to “study law and use my time fighting for men who could not strike back.” He enrolled at Harvard Law School, and became the first African American to serve as editor of the Harvard Law Review. He earned a Juris Doctor degree in 1923 and joined the Washington, D.C. bar in 1924.

As vice-dean and later dean of Howard University School of Law, Houston made that institution a premier training center for black lawyers, where his students, many of whom, including Thurgood Marshall, became important players in the Civil Rights Movement.

As the first special counsel for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Houston played a role in nearly every civil rights case tried before SCOTUS between 1930 and 1950. In Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, Houston successfully argued that since Plessy v. Ferguson required “separate but equal” accommodations for people of color, it was unconstitutional to exclude blacks from a state law school if no comparable school existed in the state.

His strategy was to prove it was costlier to create parallel schools than to allow integration, and it worked.

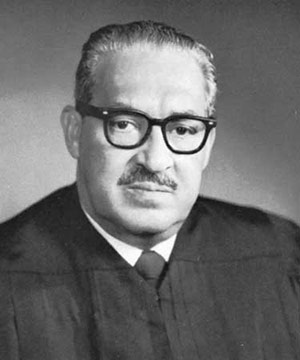

Thurgood Marshall: United States’ First Black Supreme Court Justice

Born in Baltimore, the grandson of a slave, Marshall applied to University of Maryland Law School in 1930. They denied him acceptance because of his race.

Born in Baltimore, the grandson of a slave, Marshall applied to University of Maryland Law School in 1930. They denied him acceptance because of his race.

Instead, he went to Howard University Law School and studied under Charles Hamilton Houston. After passing the bar, Marshall successfully sued the University of Maryland for refusing to admit another black student.

After Marshall led the landmark Brown vs. the Board of Education case before the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS), which outlawed racial segregation in schools, President Kennedy appointed Marshall to the Second Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals. The decisions he wrote included upholding immigrant rights and the right to privacy, and limiting government intrusion in illegal search. In 1965, President Johnson appointed Marshall to the office of U.S. Solicitor General, where he won 14 of 19 cases he argued before SCOTUS.

In fact, Marshall represented and won more Supreme Court cases than anyone else in history. He was appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1967, and retired in 1991. He died in 1993.

Barbara Jordan: First African American Woman in the Texas State Senate, Represent the South in Congress, and Speak at a Democratic National Convention

Barbara grew up in Houston’s Fifth Ward, where everyone “always knew she was gonna be somebody.” Because of segregation, she was barred from the University of Texas at Austin, so she attended Texas Southern University, the “separate but equal” Austin law school for black students. In her freshman year, her debate coach told her she wasn’t good enough to compete. She defied him by later leading TSU’s debate team to a national championship.

Barbara grew up in Houston’s Fifth Ward, where everyone “always knew she was gonna be somebody.” Because of segregation, she was barred from the University of Texas at Austin, so she attended Texas Southern University, the “separate but equal” Austin law school for black students. In her freshman year, her debate coach told her she wasn’t good enough to compete. She defied him by later leading TSU’s debate team to a national championship.

After graduating magna cum laude, Jordan attended Boston University School of Law as the only woman in her class. After she graduated in 1959, she started a private law practice in Houston and won a Texas state senate seat in 1966. When Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in 1968, she took the opportunity to honor his legacy with a stirring speech at a Houston memorial service.

Then, she became the first woman elected in her own right to represent Texas in Congress, and the first black Congresswoman to represent the Deep South. Her 1974 speech persuading Americans to support Nixon’s impeachment ranks as one of the top speeches of the 20th century. In 1976, she made history when she was the Democratic National Convention’s keynote speaker.

While in Congress, Jordan worked on over 300 pieces of legislation, many of which still stand. After she retired, President Clinton appointed Jordan to chair the U.S. Commission on Immigration Reform. Barbara Jordan died in 1996.

U.S. Laws and Landmark Supreme Court Decisions on Racial Equality

Dred Scott v. Sandford: 1857 SCOTUS ruling that African American ancestors of slaves were not citizens and had no rights or privileges except what those in power chose to grant.

Thirteenth Amendment: 1865 amendment to the U.S. Constitution abolishing slavery within the United States.

Fourteenth Amendment: 1868 constitutional amendment granting citizenship to all persons born or naturalized in the U.S., including former slaves, guaranteeing them equal protection under the law.

“Jim Crow” Laws: Between 1870 and 1965, Jim Crow laws mandated racial segregation in all public facilities, mostly in former confederate states.

Plessy v. Ferguson: In 1896, SCOTUS ruled the Fourteenth Amendment did not require social equality between races and enforced “equal, but separate accommodations” for black citizens.

Shelley v. Kraemer: In 1911, SCOTUS held that state enforcement of racially restrictive housing covenants is unconstitutional.

Brown v. Board of Education: In 1954, SCOTUS ruled that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal,” and that legal segregation was unconstitutional.

Civil Rights Act of 1964: Ended segregation in all public places nationwide and banned employment discrimination due to race, color, religion, sex or national origin.

Voting Rights Act of 1965: Banned literacy tests or tactics used to keep blacks and minorities from voting, and authorized federal oversight into state and local elections. –

Loving v. Virginia: The 1967 ruling: “Under our Constitution, the freedom to marry, or not marry, a person of another race resides with the individual and cannot be infringed by the State.”

Shelby County v. Holder: In 2013, SCOTUS invalidated the section of the Voting Rights Act allowing federal oversight to prevent discrimination in state and local elections, claiming that it was “based on 40 year-old facts having no logical relationship to the present day.”

At TorkLaw, we firmly believe that outstanding legal representation is not determined by factors such as race, sex, or religion. We are proud of the fact that our team comprises incredible men and women from diverse backgrounds, and hold to various beliefs and world views. We are all dedicated to providing world-class legal representation for our clients.